Organic Chemistry at Exum Mountain Guides

“The Snaz” on Cathedral Buttress in Grand Teton National Park is a classic Wyoming mountaineering route. Established by Yvon Chouinard and Mort Hempel in 1964, “The Snaz” is a free climb above Phelps Lake in the southerly part of the park. It slithers nine pitches up a dihedral composed of metamorphic swirls of granitic and intrusive formations—the essence of Teton geology. After 60 years of ascents from climbers and guides of every stripe, it’s become a classic trade route of the Teton Range.

In 1993, Brenton Reagan was 17 years old and on summer vacation, gearing up to follow the late, great Alex Lowe, a world-renowned alpinist and Exum mountain guide. An enviable pied piper, Lowe’s infectious passion for alpine adventure changed the lives of anyone with whom he crossed paths. Like most impressionable 17-year-olds, Reagan had no idea what he wanted to do with his life. “But then I went climbing with Alex,” he says, “and it was like, Oh yeah.”

Fast-forward to this spring. It’s a damp afternoon in Jackson, Wyoming, and I’m drinking coffee on my porch with Reagan. He’s just returned from Alaska, having taken his American Mountain Guides Association ski mountaineering exam, a two-week extended series of tests and competency requirements for working guides looking for international certification.

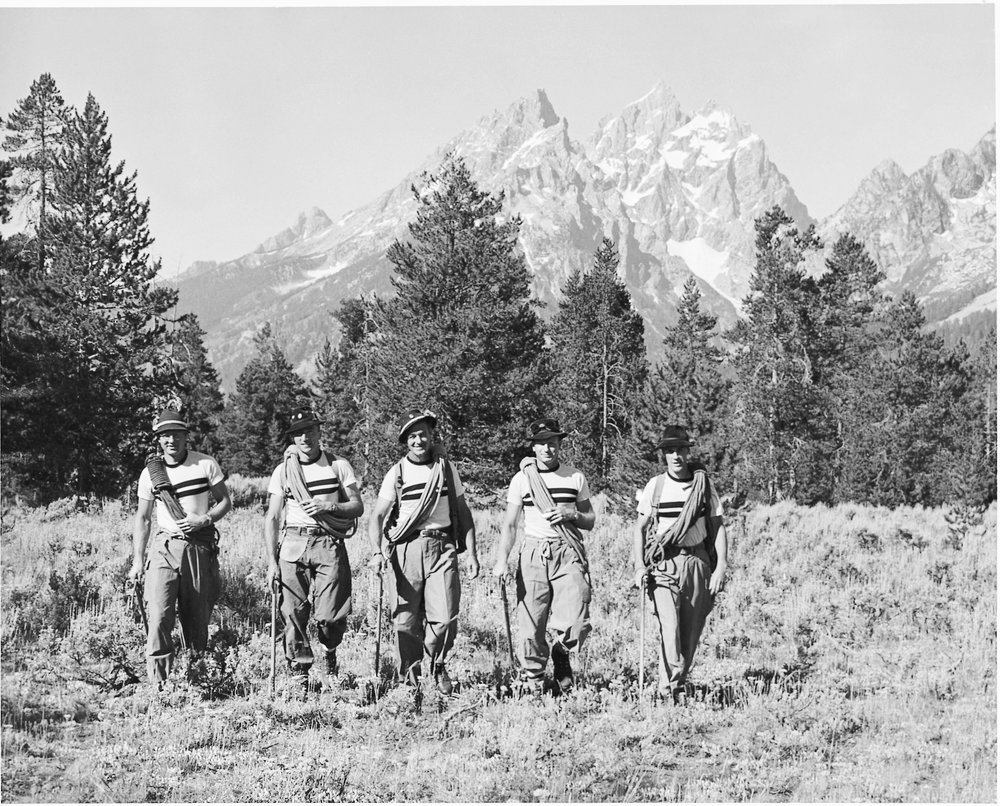

Mentorship in climbing is as old as the sport of climbing itself. It goes hand in hand with learning history, and Reagan is part of a history—the history, long and storied, of Exum climbing guides. Exum was founded in 1929 by two wayward Idahoans—Glenn Exum and Paul Petzoldt—who went to the Tetons in search of some of North America’s greatest climbing challenges. Petzoldt first climbed The Grand at 16 years old in a pair of cowboy boots. The Grand is a serious climb at 13,775 feet requiring both endurance and technical skills. With an entrepreneurial spirit to match his climbing habit, Petzoldt soon figured out that visitors to Grand Teton National Park would pay money for a guide to lead them into the park’s mountains. Soon, he started one of the first guide services in North America. Petzoldt and Exum hooked up a few years later and began what has since become known as one of the premier mountaineering schools in the country.

Glenn Exum earned the respect of the climbing world when he was 18 years old and climbed a new route up The Grand Teton sans rope in a borrowed pair of leather-cleated football shoes that were two sizes too big. While climbing The Grand in shoes that don’t fit and, honestly, don’t belong on the terrain, is notable, the real zinger is that Exum made a first ascent that included a less-than-sane jump across a gap up a ridge that now bears his name.

Petzoldt—who went on to found National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) as a pioneer in the development of outdoor education—and Exum created a mountaineering school where experience, self-reliance, and good sense formed the core of their enterprise. They departed from the European school of mountaineering where the guides “did for” the clients (sometimes tying a rope around them and pulling them up difficult terrain) and instead created a culture where guides offered instruction and the chance to utilize newly learned skills. This approach to guiding set a distinct tone at Exum where mentors have long played a pivotal role. And mentors, according to Reagan, have played an important role in his ascent from climber to guide. “I wasn’t that good of a climber or skier [when I started], but I just knew that’s what I wanted to do.” Now, 26 years later, Reagan is 43, has a wife (herself a guide), two kids, and a thriving career as a full-time guide and marketing manager for Exum Mountain Guides. And while formal education is a good thing, we’re here to mine the intangible value of mentoring and the importance of passing on history.

Exum’s guides are at home in northwest Wyoming’s Teton Range, a relatively narrow and thorny spine of faulted mountains that run north and south along the Idaho border, and it’s not an easy gig to get. Some say the only way to get the job is to be invited by guides who work there and understand the culture. Exum has employed not only Alex Lowe, but also Yosemite climbing pioneer Chuck Pratt, Willi Unsoeld (who was on the first American party to summit Everest, via a new route on the West Ridge and lost nine of his ten toes during the experience), and Bill Briggs (the Jackson legend who was the first to ski the Grand Teton)—the list is too long to name them all. Many of these legendary guides have contributed vital history and talent to climbing in the Tetons, as well as fundamental mountain protocols and practices that exist today. If you’ve ever climbed in the Tetons, you’ve probably grabbed the same holds as these greats and so many more, like (before you think it’s a male-only endeavor) Irene Beardsley—one of the pioneers for women in high-altitude mountaineering. Beardsley was an IBM physicist living in San Jose when she joined the first all-female expedition team to climb the mighty Annapurna I in the Himalayas. Beardsley credits her passion for mountaineering to her first sighting of the Tetons on a trip with family when she was a girl. These big mountains can move men and women to do big things.

The Tetons have been home to a long history of cutting-edge mountaineering and on those peaks, the foundations of good climbing practices were developed. “In the Tetons, our technical specialty is moving people through the mountains and having them perform at the right moments,” says Mike Ruth, a veteran guide with 24 years at Exum. “It’s magical how we pull it off. And so much of it comes from the formulas that were given to me when I was younger.”

Ruth is part of a generation of Exum guides who came up through the ranks and through these natural mentor relationships that developed. He learned much of the craft in Wyoming and Utah. Ruth feels that people with all kinds of educations now show up to become guides, and not much on Grand experience, so it’s harder to mentor those types of people. “It’s experience that’s the deal, right?” he says. “I don’t want the doctor with the most education operating on me. I want the doctor with the most experience.”

Before we get too reverent about the tenets of guide culture, I have to offer a minor disclaimer: mountain guides can be some of the most opinionated motherfuckers on the planet. And it’s not entirely their fault. They lead scores of inexperienced people into the merciless world of the high alpine and it’s on their shoulders to keep these clients from killing themselves. With this responsibility comes a certain status—so, to those unfamiliar with mountain guiding, a guide’s opinion tends to become gospel (whether in the mountains or, well, anywhere, depending on the guide). They constantly have to repeat the most basic mountain rules, over and over, ad nauseam. Because the client’s safety is paramount, mountain guides develop strict policies of “go” or “no-go” safety checks and constantly have to look over their shoulders to make sure the client isn’t doing the very thing they’ve told them not to do. All day long. All month long, if you’re on a big mountain. Good judgment is vital, and even minor accidents in the hills can have dire consequences. Guides also have to handle the egos of high-paying clients who don’t like the whims of Mother Nature denying their summit bids, so guides are constantly charged with being part diplomat, part babysitter, part entertainer, and part caregiver, all within the span of a day’s work. For the same reason their heels get callused from hiking long days under the punishing sun, so too do their mannerisms.

One of Reagan’s longest relationships to mountaineering can be summed up in two words: Wesley Bunch. A tall, lanky North Carolinian drink of water, bunch moved to the Tetons in the late ‘80s after taking a climbing trip west with a friend and professor from college. Bunch had felt the pull of mountaineering since his first roadside climb. The math was simple. “Unlike surfing, like when you go to the beach,” says Bunch, “nobody ever says, ‘you should’ve been here yesterday, Wes.’” And that was it. “If I was up to it, I could always have an adventure climbing.” And one of his greatest adventures has been mentoring Reagan. But a mentor worth his grime most likely had his own mentor at one point in his development.

In his early Jackson days, Bunch sought more experienced climbers and skiers to take him into the mountains as well, namely Tom Turiano, a prodigious skier, Exum guide, and author of several books about climbing and skiing throughout the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. “I was lucky that Turiano saw a rabid trailbreaker in me if nothing else,” he says. Some of a mentee’s role comes in the form of unorthodox responsibilities. “Tom would always insist on wearing his leather boots in those early days,” says Bunch, who recalls a few overnight trips under severely cold conditions. “On more than one occasion he’d have to put his toes under my armpits to warm them at night.”

For years Bunch climbed a lot, and skied throughout much of the northern Teton Range over several winters with Turiano and others before getting the nod to show up at Exum’s guide training day. He’s been a mountain guide ever since.

“Mentorship was big in those days,” says Bunch. “I think it has a lot to do with people’s vision of how important the history is to climbing. If you’re not interested in history, you’re not going to be that interested in a mentor, you’re not going to be interested in the experience that he’s going to give you that was passed on through his mentors, which is history. That’s the sort of thing that certifications can’t teach you—those nuances that turn guiding into an art instead of just a skill.”

Renny Jackson is a fixture of the Tetons. A Grand Teton Climbing Ranger for 34 years before swapping hats to become a guide in his “retirement,” he is the co-author of A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range with one of his mentors, Leigh Ortenberger, and has won the Valor Award for bravery three times from the Department of the Interior. “I’m a big proponent of studying history,” Jackson says. “I think it adds a lot of depth to climbing and mountaineering. I get surprised by folks who don’t know what’s gone before.”

Jackson has seen the devastating results of misadventure, and knows as well as anyone the benefits of an empowering apprenticeship. “If you’re lucky enough to get someone with a lot more experience than you,” he says, “and they’re teaching you all sorts of things, very critical things, and you’re seeking objectives in climbing, mutually desired objectives, that’s very cool. The rewards are obvious. They’re showing you the way, and they’re sharing in the reaping of the benefits. You can’t put a price on that.”

It’s an education of mastering technical systems, personal politics, lifestyle choices, physical suffering, and real life consequences—this life of apprenticeship. Reagan recognized the value of it early on. Minus the golden curled locks, Reagan is nothing short of Wes Bunch 2.0. He left his native Georgia for good in 1999, moving to the Tetons to begin shouldering materials and supplies seven miles up Garnet Canyon for clients vying for a piece of Teton glory. “My portering wages went back to Wes to take me climbing,” says Reagan.

The two became fast friends and spent years getting into the hills together. “We were able to do things that were off the beaten path that I wanted to do,” says Bunch. “And I had a client (Reagan) who was willing. He didn’t come with an agenda. We hung out and he observed, and I talked about things I thought might be important and safe, and he either picked them up, or he didn’t.”

Exum has long been a fraternity of journeymen climbers who guide to pay for their climbing livelihoods. They have always been climbers first, guides second. Job positions at Exum have always hinged on references. Hard skills and accreditation are important, but you also need to be on the same vibe with Exum culture. “I honestly rely on references more than anything,” says Nat Patridge, co-owner of Exum Mountain Guides. “And what’s most important to me is, will this person work well at Exum and uphold the cultural values we have here, be an educator, and want to co-guide and work with a lot of other guides?” Hard skills and accreditation are important, but you also need to be on the same vibe with Exum culture. “I honestly rely on references more than anything,” says Nat Patridge, co-owner of Exum Mountain Guides. “And what’s most important to me is, will this person work well at Exum and uphold the cultural values we have here, be an educator, and want to co-guide and work with a lot of other guides?”

Maintaining that culture is a lot of work and the way you mentor is going to say a lot about the way you guide clients. Both mentoring and guiding take patience and a lot of self-awareness. “You have to want to be somebody’s mentor,” says Bunch, “and they have to want you to be their mentor… I think I wanted to be a mentor more than I ever knew. And I think that if you want to be a mentor, you’re going to want to be a good guide.”

Maintaining that culture is a lot of work and the way you mentor is going to say a lot about the way you guide clients. Both mentoring and guiding take patience and a lot of self-awareness. “You have to want to be somebody’s mentor,” says Bunch, “and they have to want you to be their mentor… I think I wanted to be a mentor more than I ever knew. And I think that if you want to be a mentor, you’re going to want to be a good guide.”

One of the first rules of guiding is to provide a safe and pleasurable experience for your clients. “And,” adds Bunch, “to teach them that hardship and difficulties are a part of the game. And part of what you get out of it is going to come from how you handle those difficulties—suffering on expeditions, cold weather, the things that make climbing something other than watching TV, or Oprah.”

“Wes taught me how to suffer,” says Reagan, grimacing for effect. “He was the one who really taught me how to embrace hardship.” To better prepare Reagan for his first trip to climb Denali, Bunch took him on a 10-day slogfest (ski trek) into the remote Titcomb Basin of Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains in the middle of bitter January. “That’s suffering,” says Reagan.

Enter Michael Gardner, a 25-year-old guide who’s been working for Exum for only four years. But here’s the catch: Michael grew up spending every summer since he was a child at Guides’ Hill, Exum’s inholding employee housing at Jenny Lake in Grand Teton National Park. A cadre of cabins, including those of the Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers, clusters off a gravel road about a mile from the Lupine Meadows trailhead, the departure point for many alpine climbs, including those on the Grand Teton. A short walk to Jenny Lake, a hop into Cottonwood Creek, or a stroll through endless acres of valley meadows form the backdrop of summer for many kids whose parents work and live in the Park. To call it an idyllic pastoral childhood doesn’t even come close.

Michael’s father, George Gardner, was an accomplished guide and teacher from the south side of Chicago, who made the pilgrimage to Wyoming every summer for 28 years to guide for Exum. A solid brick in the proverbial Exum wall of prowess, he was a steadfast guide and engaging presence amongst the mountaineering community.

Reagan’s memories of the elder Gardner echo those he has for Alex Lowe. “I think we all like to believe we have a spiritual connection to the mountains when we’re out there,” he says. “I think some of us think it’s bigger than it is, and it probably isn’t. But with somebody like George, he really had it. He was just really talented, and had the right balance of family, life, and spirit of the Tetons. I think we all looked up to George because his take seemed to be the most authentic. He was beyond, for sure.”

In July of 2008, George was soloing the Exum Route on the Grand Teton after bringing clients to the Lower Saddle, a common stopping point for guided parties attempting The Grand. Many guides often scamper around the mountain after the hike to get a little personal freedom. While covering ground on the ridge, he slipped and fell to his death under the waning summer sun. Michael was 16 years old.

His passing was a devastating blow to the climbing and guiding community. “George’s death was just horrendous,” remembers Jackson. “It happened right in the middle of guiding season. I got the call, and was the person who ran the recovery. I went up with three or four other folks, got George, and brought him down. My daughter Jane and Michael were basically teenagers. It was just rough, you know.”

Reagan mirrors those sentiments. His own father died prematurely of lung cancer in 2003, when he was just 28, leaving a void for him to fill as well. “George was a huge influence on me after my own dad died,” he says. “Not to take anything away from Michael, but I can remember three times in my life when I cried the hardest: my dad, my first dog, and when George died.”

Despite the heartache George’s untimely death brought to countless members of the Exum community, Michael himself speaks about it with stoic resolve of someone beyond his years. He also recognizes something that the Exum community knows too well—the lives they’ve chosen run with risk. “My dad wasn’t the first person close to me who died in the mountains,” he says. “He was definitely the closest. But living around that community and lifestyle my whole life, when things like that happen, I wouldn’t say you come to expect it, but you come to recognize it as inevitable. It’s not necessarily if and when, but who and when.”

That’s not to say the event didn’t shake him to his core—quite the opposite. Michael didn’t climb for the next two years. Up until this point in his life, his only climbing partner had been his father. And he was gone. “I wasn’t really willing to allow anybody else in as a climbing partner, mentor, or teacher right away,” he says. “Climbing bonds and partnerships are so sacred to begin with, that when you have one and it’s with your father, it’s sort of a final note for me. I didn’t see myself climbing, not for fear of death or accident, but simply because I didn’t want to share that partnership with anybody else.”

Nevertheless, Michael returned to the Tetons the following summers, living illegally at Shadow Mountain, where car camping scofflaws could live on the sly and continue to work within the Park. Though he wasn’t yet employed with Exum, and his father was gone, Michael still felt compelled to hang out at the guide stronghold.

Mike Ruth had been a personal friend of George’s, and has known Michael since he was a young boy. He too lived and worked out of Guides’ Hill every summer, intuitively keeping tabs on Michael those following years. “With the old-school guides you had to be very perceptive of everything going on around you, all the time,” he says. “That’s your number-one tool, not knowing how to tie a munter mule knot.”

Ruth was instrumental in getting the young Gardner to spend more time around Guides’ Hill after his father died. “He was the keeper of a lot of stories about my dad, which were pretty profound for me,” says Gardner, “and I recognized his impact on the community around me at Exum. As the son of somebody like him, I didn’t necessarily know what he had done—how much his clients enjoyed him, how well he interacted with people at Exum, and the legacy he left.”

“Michael is that legacy,” says Patridge. “His father worked here and was revered. And he is revered just as a result. He stands on this platform of already being respected and so he has this voice as a really young man who garners a lot of respect. And he shoulders the responsibility really well, and with a lot of humility. But he’s empowered to speak out and really shape the tone of discussion in a kind way. That, and he’s such a damn good athlete.”

By the time Michael was a teenager, his family lived in Ridgeway, Colorado, and George taught at the local high school. Michael was a competitive freeskier and was named one of the best skiers under 18 by Powder magazine. Now, at 25 years old, he’s already climbed several times in the Himalaya, taught climbing at the Khumbu Climbing Center alongside the likes of Renny Jackson, and last year he made the fourth ascent of the famed “Fathers and Sons” wall on Denali in the Alaskan Range, albeit a new variation called “Mother’s Day.” For those in the know, it’s a big deal. “It’s probably worthy of a Piolet d’Or Award,” says Patridge. “And yet he doesn’t broadcast it.”

How you act off the wall also matters. “He’s proud of that line,” Ruth says. “But he doesn’t spray about it.” And for long-term guides like Ruth, perspective matters a lot. “I mean, it’s just a thing. We’re not curing cancer. We’re not solving great problems. As much as anything, I admire Michael for the way he carries that climb off the climb.”

The common bond between Gardner and Reagan is the shared history, and the awareness of their roles in it. And if mentorships are going to continue to take root, an appreciation of history is the water that sustains it. Exum, by default, is a bastion of the Teton mountaineering record. And Reagan and Gardner are in the enviable position of being in a special place and time, knowing that they are a part of a unique story in the American West.

It’s still raining, and our coffee cups are empty. Reagan is beginning to stand because his wife is watching the kids while he waxes on about guiding lore. He has to leave soon. “We all got into these jobs because we don’t like being told what to do,” he says. “And good mentorship helps the pacing of your growth as a guide. If you can give advice without it being a directive, that person is going to be more open and willing to embrace that information. It’s all a part of gaining wisdom and knowing when it’s okay to pass on some of that information in small pieces when needed. It gives us the insight to slow it down and go at the right pace. That’s what Wes gave me. And Mike Ruth.”