As billows of smoke rise over the mountainside and dark clouds begin to settle over the Alaskan wilderness, eight men are loading up their gear in preparation to fight a raging forest fire. This is just another day at the office for the smoke jumpers of Alaska – the individuals who risk it all to protect great spans of wilderness areas.

In early March Jamie Mayor, an Alaskan smokejumper who spends the rest of his time in Salt Lake City, finishes his final stages of packing. He pets his dog Charley and kisses his girlfriend Jacki goodbye. He is returning to Alaska for another season of fire fighting and will be back in October, just in time for winter. Jacki and Charley are used to this routine though; six to seven months away from home is a pretty typical routine for smoke jumpers. The sacrifices are high but the dedication is higher.

Mayor describes Rookie training as fast paced and stressful. Each year there are about 150 applicants and only six to ten spots that are filled, he explains. The training usually lasts for four to six weeks, with a drop out rate of around 40%. For the few that make the cut, this is just the beginning of a grueling six-month stretch.

The eight men selected for the first jump have to be ready for the fire call. When the alarm sounds, the crew has two minutes to suit up and be on the plane. If you’re left behind, you’re assigned various tasks at the base, including a rigorous training routine to maintain the high level of fitness required for the job.

“The Alaskan smokejumpers also run the largest civilian paracargo operation in the world,” says Mayor. “This is what occupies most of my time when I’m not on a fire. Fires in Alaska typically are not near roads, so paracargo is an efficient and cost effective way to get supplies to the people on the ground. We can airdrop over two tons of food and water in one trip. We can deliver inflatable zodiac boats, ATVs, pumps, hoses – just about anything really. The job never sleeps.”

Teams jump in Kevlar jump suits that are equipped to hold everything the firefighters need while on the ground. The pocket across the back of the suit typically holds a tent, rain fly, and small down jacket, while the gear they use on the fire is strapped to the front of their suit for jumps. “The jumpers usually maintain all of their own gear too,” Mayor explains. “There is always sewing to be done and repairs to be made.”

Once the crew hits the ground, all of their remaining gear goes into a large backpack, while their heavier equipment such as chainsaws, pumps, and tools are dropped down to them from the cargo plane. Since there are only eight men in each jump, they are expected to look out for each other and have a plan in place so every member of the team can act quickly and efficiently. “Plan” is a relative term in this industry though. Sometimes these guys jump into a situation planning to stay for just a few days, only to find themselves continuing the firefight weeks later.

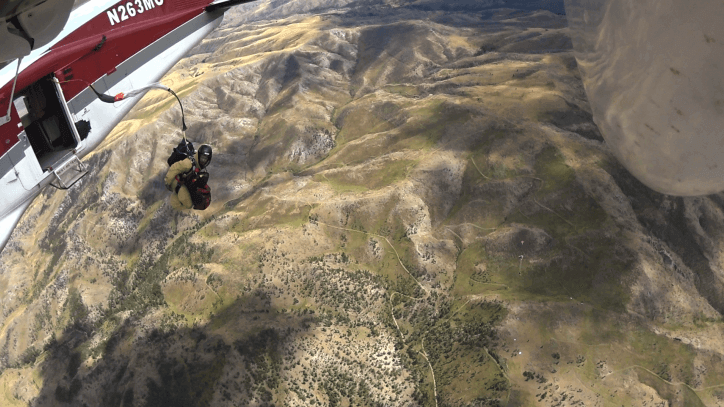

Upon completing their assignment, the team relies on helicopters and planes to get them out of the fire zone. “There are not many roads through the Alaskan wilderness,” says Mayor, “so cutting out a heli-spot with chainsaws is typical.” After the team has cleared a landing pad, a helicopter sweeps in to grab the men and takes them to the nearest village or town, where they are picked up by plane and taken back to Fairbanks – their home base for the summer.

In case of a medical emergency on the ground, half of the jumpers are certified Emergency Medical Technicians, or EMT’s. Helicopter evacuation is not always (or even often) a possibility in the situation these crews get themselves into. It’s crucial to have men on the ground that can fight fires and treat burns, fractures and other injuries that are a big part of the risks of this job.

“Wildfires have become more consistent each season,” says Mayor, so the smokejumpers have begun to experiment with new technology that will make each jump safer and quicker. “The use of drones and GPS technology have been talked about a lot,” Mayor notes. “Some fires are too smoky to get helicopters anywhere near them.” Right now drones are primarily being used to map territories so cargo can be flown in and delivered men at specific GPS coordinates.

The demands and risks of this job are undeniably high. Mayor knows it. His girlfriend Jacki knows it. We know it. Anyone who’s been near a forest fire, which is a lot of us across the Western United States, know it.

“How do you balance this stress in the off seasons?” I asked.

“It’s the typical seasonal worker kind of thing,” said Mayor. “Skiing, snowboarding, hunting, fishing, and a lot of traveling. A handful of the guys that stay in Fairbanks in the winter are fur trappers or dog mushers.”

These guys definitely deserve their time to play.

BigLife would like to thank Mayor and all firefighters for risking their lives to save our giant playgrounds.