Close your eyes. Let your mind drift to your favorite place in the world. What do you see? Think about all that inspires you about this place. Ask yourself what you would do to protect it from threat. What if you had the ability to take action to protect this place and see change occur in your lifetime? That opportunity is here, and today we have the chance to help permanently protect one of the most unique, extraordinary places on planet earth.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is the largest National Wildlife Refuge in the country, whose establishment began in the 1950’s when a Sierra Club journal article was published calling it, “The Last Great Wilderness.” It is home to an incredible biodiversity of plants and animals, as well as the Gwich’in Tribe. Located high above the Arctic Circle, ANWR is a contentious landscape due in large part to its division of lands. Some regions of ANWR have been protected as wilderness, part of the area is administered as a refuge, and the most northern section of the region, known as the 1002 area, was set aside by Congress due to the areas potential for oil and gas extraction.

The Gwich’in Tribe has called ANWR home and has respected the region as sacred grounds for millennia. The Tribe- their health, their livelihood, and their spirituality – are inextricably linked to these lands. The name Gwich’in literally translates to “people of the caribou.” The Tribe has lived closely alongside the Porcupine Caribou herd since their creation – they rely on them economically for sustenance, as well as culturally as the centerpiece of their communal and spiritual practices. They believe that every caribou has a little bit of human heart, and that every human has a little bit of caribou heart. The result is an environmental ethic that runs deep within the Tribe as they pay great respect to the caribou and the land that supports them.

The first hints to drill for oil in the 1002 area started forming in the late 1970’s, but it wasn’t until a 1986 report by the US Fish and Wildlife Service that recommendations were formally made to open the area for oil and gas development. The push to open the 1002 area for resource extraction seemed inevitable, until the Valdez oil spill in 1989 brought a public outcry about the potential environmental effects of drilling for oil in fragile environments. The push to drill in ANWR stalled, but politicians and the oil industry maintained their position that oil extraction in the area was a viable option for the future.

In 1988, hearing that the land that is central to their existence was under increasing threat, the Gwich’in Tribe held a gathering of their people for the first time in over 100 years. Since the 1002 area is also the calving grounds for the Porcupine Caribou herd, the Tribe affirmed a collective stance to protect the 1002 area and ANWR as a whole. Since the development of this controversy, scientists have noted that drilling in the 1002 area will alter the environment to such a degree that the ability for the caribou to birth and nurse their young will be compromised and the herd will not be able to survive. Culturally speaking, if the caribou die, the Gwich’in and their way of life will disappear as well.

In 2015, President Barak Obama took a notable environmental stance when he recommended to Congress that areas in the Arctic Refuge, including the 1002 area, be protected as wilderness. Congress has not yet acted on Obama’s recommendation, but the President still has the chance to leave a lasting legacy that promotes human rights, climate change advocacy, and biodiversity protection by creating a National Monument for the Arctic Refuge before his time in office is complete. That move will also support the potential future wilderness designation- the strongest protection this land can be bestowed under US law.

This past July, the Gwich’in held their 15th biennial gathering, born from the 1988 gathering in Arctic Village. The Tribe was joined by friends, advocates, and other outsiders invited to participate. As a professor at Sierra Nevada College I have been fortunate to facilitate a cultural immersion-sustainability course in Arctic Village for the past three years based on an invitation from an elder in the Tribe, Sarah James. Sarah has become a spokesperson for the Arctic Refuge, traveling to all corners of the globe to share the story of her Tribe and their efforts to defend ‘the sacred place where life begins’. She has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize. Her words are as real as the integrity of the land she inhabits at the foot of the magnificent Brooks Range.

“This is my way of life,” says James. “We are born with this way of life and we will die with it. It never occurred to me that something had to wake me up to do this. Nothing magic happened to me. Our life depends on it. It’s about survival; it’s something that we have to protect in order to survive. It’s our responsibility. It’s the environment we live in. We believe everything is related.”

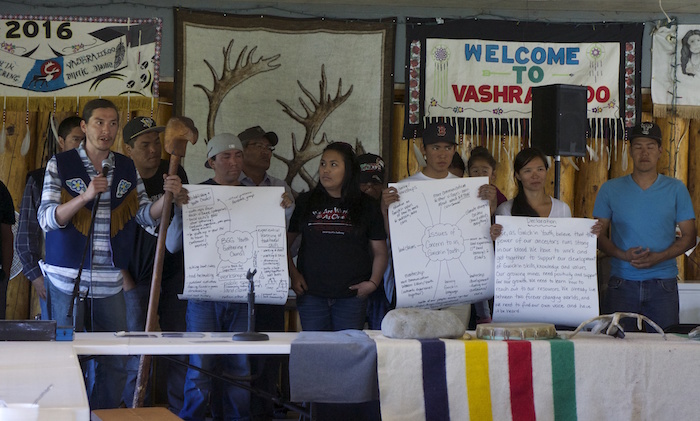

During this year’s gathering, many people spoke and many issues were covered. Each speaker offered prose layered with passion. From the Land is Life party that brought Indigenous women leaders from Ecuador and the Philippines to share stories of their struggles and victories, to the youth leaders of the Gwich’in that spoke about their emerging role as defenders of their people’s cultural traditions and land, every second of the gathering was filled with active hope. Each night, after hours of workshops and testimony that would put faith in the faithless, the community hall would transform into a dancehall where music played into the wee hours of the darkless night.

Outside, the backdrop of ANWR radiated in a sublime, perpetual alpenglow uniquely situated to polar regions of the world. As a visitor, you could feel the words of the speakers in the mountains. Nothing could be more important than protecting this land and the way of life these people have created.

As the gathering concluded, I realized that permanently protecting ANWR was less about this one issue, and more about how important this victory could be for those most affected by its destruction, and how the victory would impact the many other people and places around the world that are facing similar threat.

Since wilderness designation is the strongest protection that can be offered to this land, and that push has stalled in Congress, many advocates are supporting the next best next step, which is to establish a National Monument in the region. This act will help the Arctic Refuge defend the current threat of drilling, while bettering its position for a wilderness designation to be established in the future.

The beauty here is that the potential for this to happen is one signature away. One of the strongest powers held by the president is the ability to establish National Monuments. Before Obama’s time in office is done he can make this happen. He has already protected more pubic lands than any other president, and has made strong claims that conservation and climate change are not only two of his top priorities, but his lasting legacies. Although he has made some solid strides in these departments, permanently protecting ANWR would be one of the most noteworthy achievements of his time in office.

Past estimates have suggested that drilling in ANWR could provide about six months of useable oil for Americans. However, most Americans would never benefit from this resource because the oil would most likely be shipped elsewhere due to the remote geographic location of ANWR.

Think about that. We are looking at the potential to destroy land that is regarded as some of the most pristine in the world, while also destroying the cultural traditions of a Native American community, for a few months worth of dirty energy. To me, it seems impossible to get behind this idea.

The “Keep it in the Ground” campaign has gained massive traction in recent months, with major US universities such as Yale divesting from companies that profit from fossil fuel activities, and many more diverse institutions arguing to keep fossil fuels in the ground as a way to curb further warming of the global atmosphere associated with the use of carbon fuels. This campaign discourages the use of fossil fuels while incentivizing research and the development of renewable sources of energy – a big win for environmentalists, not to mention pretty much anyone who appreciates life as we currently know it.

In addition to climate change, the fight to protect ANWR also involves the respect of a culture and the sacred places of Indigenous peoples. No move from a conservation standpoint could be stronger.

I know I am not alone in recognizing that the issues represented here are diverse and layered, which is why I feel this effort is so monumental. I use oil just like most of the rest of the world, but at some point we all need to recognize that this finite source of energy is just that, finite. Coupled with emerging energy technology and an accepted global awareness that humans need to curb their use of fossil fuels and their corresponding contribution to a warming planet, this struggle to protect the Arctic Refuge couldn’t be more significant. It stands for something much larger both environmentally and socially.

Close your eyes. Go back to your vision of a place that rests close to your heart. Maybe you can feel, for just a brief moment, how the Gwich’in Tribe feels about their homeland.

As members of the outdoor community, so many incredible places matter to us, but my time with the Gwich’in Tribe has taught me that we cannot assume these places will always be there and we certainly cannot fight our battles alone. We must build affinity, across diversity and understand how the struggles to protect the Teton Range can also be found in the fight to protect the waters of Lake Tahoe and the necessary work to clean the air of the Wasatch. This is as symbolic of an act as any – not just to protect a place you want to visit and experience at some point, but to take a stand for the values that matter to you the most.

I understand that ANWR might not be your special place out there in the world, but this is an act of collaboration – one that might come back to help your landscape and your community sometime in the future. You can make a difference, and that difference might make a bigger impact than you think.

Learn more and take action to help protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge:

- League of Conservation Voters: Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Petition

- We Are The Arctic: Tell The President & Congress to Protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

- Alaska Wilderness League: Help Flat Sandy as she tours America in support of the Arctic Refuge

- Change.org: Protect America’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

We Are The Arctic: Human Aerial Art Piece

Courtesy of Spectral Q/ Florian Schulz